|

I often talk in my yoga classes about effort on the mat in order to have effortlessness off the mat. This could also be stated as working hard in one area of life in order to make other areas work more efficiently.

I also often expound upon building inefficiency into your day to create more movement opportunities. Paraphrasing biomechanist Katy Bowman, "efficiency doesn't save time; it reduces movement." So which is it I want to instill in my students and clients? Efficiency? Inefficiency? Honestly, it's both. I recently got deluged with requests for information about private sessions, upcoming events, shoes, waiting lists, classes. It has been incredible to experience, but it also forced me to see where inefficiency was hindering my ability to function, my ability to help all these people. So many of them initially needed the same information. Rather than copy and paste the same content into 100+ emails, or try to send one email but need to add 100+ names to my contact list to do so, I finally figured out to put all the information into an Out-Of-Office reply. This allowed me to respond to all the individual requests (booking private sessions) in a more reasonable manner. As I began meeting all these new clients, I also noticed that many of them needed similar descriptions of movement work in the follow-up emails I send. I finally realized I could copy much of that information into a large document, copy and paste specific exercises into individual emails, and then add the details relevant to the specific client. This saves me an enormous amount of work. Each of the above is an example of effort now for effortlessness later. Each example created efficiency. On the mat, in a movement practice that looks a little different. If I teach a pose to you that creates strength or mobility where it has previously been lacking, that pose will not be an easy pose for you. It will be a lot of physical effort for a very brief period. But that effort, repeated over time, will eventually lead to you having the strength or mobility you have been missing. That new stability or flexibility or alignment will become unconscious work for your body because of the effort put in during the actual pose. This is creating efficiency in the body. We count on our bodies to do a certain amount of unconscious work. If you had to consciously think about every muscle, every action required to do a daily task such as brushing your teeth, it would be extraordinarily draining. Do that for every part of your morning routine, and you'd be ready for bed before you even got to eat breakfast. It is clear then that a certain level of physical efficiency is desirable and necessary. The flip side of that, however, occurs when we lose dexterity, strength, mobility, due to all the ways we've made our lives efficient. Much of the required movement our ancestors needed to do to get through their day has been eliminated in current Western culture. We do not have to spend all day in search of food or creating shelter. We do not have to walk anywhere. We do not even have to drive anywhere to buy the food we eat. Many, many people order groceries on line and have them delivered. I have worked with clients who prefer slip-on shoes because then they don't have to bend over to put them on. They won't have to tie their shoes with fingers that don't work as well as they used to. That same person comes to me to relearn how to bend over. I give them exercises to rebuild dexterity and strength in their fingers. And then I tell them to bend over to put their shoes on every day. Buy tie shoes and use their fingers every day. That little bit of efficiency (slip-on shoes) has created weakness and inability in their bodies. Most people put the most used items within reach in the kitchen, just above or just below waist-height. If an item gets stored down low, many folks choose to add roll-out drawers in the cabinets. Those same people have stiff upper backs and shoulders from never lifting their arms. They cannot squat down. So they start going to the gym or classes to relearn those movements. Or they simply give up on squatting, lifting something off a high shelf, etc. because they're "too old." Tying your shoes may seem like a small action, but over days and months and years, that action allows a person to maintain specific abilities. Bending over, getting closer to the ground, reaching up high --- all these are part of how humans are designed to function. Stop using one body part and it stops working well. Over the long haul, these seemingly small deficits create bigger and bigger health risks. (Picture the Tin Man rusted stiff in the woods in The Wizard of Oz. Not a perfect analogy, but it'll do.) Building in inefficiency is a way to undo the damage of our sedentary lives. These two topics --- effort for effortlessness, and inefficiency for more movement -- actually can cycle themselves together. They are not strictly opposites. Over the past few years, I have been gradually working on getting closer to a full squat. It started with working on some specific poses to increase the strength around my knee and hip joints, to increase my ankle flexion, and to lengthen my tight calves. It was a good bit of effort on the mat for a few minutes every week. While my heels don't yet reach the floor, I can comfortably get all the way down into a decent squat (AND get back up). It took a lot of effort in focused moments over a long period of time. Effort over time for effortlessness now. Because of that previous effort and the resulting ease of movement, I can do the following: I squat down in the early morning to get the dog's leash and a poop bag, then I squat to hook the leash on the dog, to put my shoes on, to pick up the dog poop, to undo her leash, to take my shoes off again ... if I do all that, I've squatted down six times before I've had my morning tea. Throughout a day, I easily squat 30 - 40 times. It takes me a tiny bit longer to get down and back up than it would to bend over or to store things closer to my standing reach. Squatting down is inefficient. But here's where they connect: I don't need to find time to get to the gym to do 30 - 40 squats every other day. So ... inefficient = more efficient. I fully encourage you to do the real work now to create ease in the future. Weak ankles? Learn what you need to do get more stability and strength at that joint. Stiff hips? Learn what you need to do to bring more mobility to the area. And don't mistake ease/effortlessness for doing as little as possible. Build inefficiency into your daily life for better movement, better health. (NOTE: I am aware that non-Western, non-wealthy cultures do not have the same problems. I am also aware that not all physical limitations come from inactivity. I am talking to and about the people I see most in my classes and private practice, people of a certain amount of wealth in a particularly sedentary culture who are struggling with aches and pains related to all of the above.)

0 Comments

"I can't balance."

"My knees don't bend that far." "I'm too old to climb." I hear these and many other statements from students and clients and even the occasional passerby who sees me walking along a fallen log or squatting down to get something. I understand the feeling. A couple years ago, I started to clean the gutters and I felt unsteady climbing the ladder. I though, "I'm too old for this." But then I realized, it wasn't age that made me unsteady on the ladder. It was the fact that I hadn't been regularly climbing anything for many, many years. When my students tell me they don't balance well, I usually respond by asking how often they balance every day. The answer is usually "not at all." Why do we think we'll be good at something we don't do? Trying to relearn an old trick takes time. Little kids challenge their balance all the time if allowed to play. They walk on the curb or low walls. They play games demanding hopping or freezing in funny positions. They simply opt to try and stand on one foot. When is the last time you did that? Same with squatting down. If you have a limited relationship with the ground and choose to sit only on chairs and sofas, your hips, knees, and ankles have lost mobility and strength. Regaining ability in all those joints means starting very gradually with work designed to move your body a little bit more in the direction of squatting. It doesn't mean force yourself down into a squat today. After that experience on the ladder a few years back, I made a point to climb up onto chairs and stepladders more often. I gradually became accustomed to how my body moved and how I balanced. And I can tell you that climbing a ladder no longer makes me feel old. I got better at it. Whatever you do a lot of is what you get comfortable doing. If you want to move differently, you'll have to start moving differently. Give yourself time. It may seem as though balance or climbing or squatting come easily to young bodies, therefore you have to be young to do that. In reality, it comes easily to bodies that balance, climb, and squat regularly. I teach classes, workshops, and retreats. I see private clients. I sometimes help out friends and family with pains or movement-related questions. People come to me with a wide range of abilities and limitations. Some folks are trying to run a marathon but getting stalled at 16 miles due to some seemingly new joint issue. At the other end of the spectrum, I work with people with chronic diseases or conditions who are struggling to stand without pain or build strength without exhausting themselves. If I don't pay attention to the particular person in front of me, they could get hurt. Alternately, if the student/client isn't clear about their limits or honest about their pain, they could get hurt. Either way, the only one at risk of injury in these settings is the person I'm trying to help.

For the long-distance runners, I'm looking at their gait, learning about old injuries or chronic issues, and discovering what isn't moving well. The new pain is probably due to an imbalance that could withstand a certain amount of use, but reared its head when asked to do more. Once I figure out the imbalance, the athlete and I can figure out what movement patterns are creating or exacerbating the problem. Then I help them create new movement patterns, using weight-resistance or introducing other ways to rebuild strength or mobility. The goal is to move better with less chance of injury. My client who is housebound and easily exhausted (disease-related), I remind to look up. Lifting her eyes to the horizon brings her torso upright without the same effort as telling her to "sit up tall." Maybe we add wiggling toes or moving fingers. The goal is figuring out how to keep more of her moving and keep her energy up. Too much will deplete her. With both of the above scenarios, it's one-to-one time. I'm checking in, seeing what's too much, what helps. I am ensuring, to the best of my ability, that no one gets hurt in pursuit of healing. In a class situation, I can only do so much checking in or asking. I do try to attend to everyone, but there numerous people in a class and I can't see everyone at all times (though I'm quite good at recognizing who needs attention when after getting to know my classes). It is the students' job to listen to their limits and stop or modify as needed. That can be hard when you're new and trying to figure out what the heck I'm teaching. You may not even be aware of pain signals in your body if you've been dealing with pain for any length of time. (Thank you, Nervous System, for numbing some of those nerve endings so we can function when we've been experiencing chronic pain.) Another challenge inhibiting self-awareness is group dynamics. People really want to do what the rest of the class is doing. We don't always want to come out of a pose early or do a modification. We don't want to appear as though we can't keep up. If I teach a pose, that's the pose everyone assumes they should do. If I offer a modification to the group, very few will actually take me up on it. But many of us should be doing the modified version. As a result, I often teach the modification to the entire group. Last weekend, I suggested sitting up on blankets or bolsters at the start of a workshop. The people who most needed the added support wouldn't take the suggestion. Rather than call anyone out by name (which I have also been known to do), I changed the instruction. I made everyone get a bolster. The relief on the faces of those who needed it and wouldn't do it earlier was visible once they were seated in a better position. So much resistance to what's good for us. I get it. Our whole culture teaches us to "Just do it," or to "push through it." Who doesn't know the phrase "No pain, no gain?" In yoga, teachers talk about working at your edge. Lately, this has come to mean working at the most extreme sensation. But working at your edge isn't pushing yourself to the point of pain. It's working at the beginning of instability or unfamiliarity. Stepping a toe outside of your comfort zone is a far cry from jumping off a cliff. I often see students grimacing through a pose even as I have just told them, "If it hurts, stop." In my opinion, getting on a mat, on your own or in a class setting, but ESPECIALLY in a class setting, you need to be your own teacher, checking in and asking if this is truly okay, aware of your personal needs and issues. As a student, you need to own your shit. And if that means you don't hold a pose as long, then don't. If your arm doesn't go over your head due to a shoulder injury, don't put it there. even if I just told the entire class to lift your arms overhead. I work almost exclusively with grown ups. You don't need my permission to not hurt yourselves. Following my general instructions when they don't apply to you personally could lead to injury. As much as possible, I teach to who is present. I try very hard to watch everyone closely. But with a wide range of experiences in the room, I can only do so much. I can't always tell if you've pushed yourself too far. Soooo I will offer modifications. I will give you permission you don't actually need to come out of poses early. If I don't offer any modification and you realize you need one, you can and should ask for one. It doesn't help me in any way if you override your own body's signals to stop. It does, however, have potential to harm you. You have to go home in your body. I don't. Use the wall.

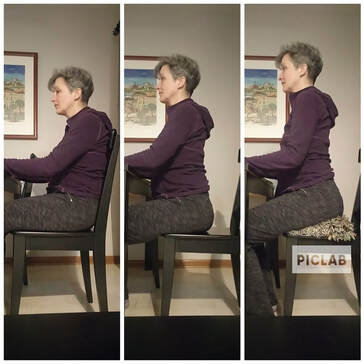

Don't use the wall. What's the difference? Depends on what you're working on. If you struggle to balance, I often suggest using the wall while you learn how to engage your body in the pose. Whether you are working on a Warrior pose or in a single-leg balance, if you are mostly worried about falling over, you will hardly be able to do any other work while you struggle to balance. In fact, that struggle might include a fear of falling which adds unnecessary tension in your body. Hard to work on pressing down into your heel or straightening a leg or lifting up through your spine if you are mostly focused on whether you can stay upright. On the flip side, if you only ever work at the wall, you will likely develop a reliance on the added support. You miss the opportunity to wobble and to regain your balance after that wobble happens. That wobble, that instability, is important. Instability wakes up under-utilized muscles. Instability also creates plasticity in the brain. We WANT those things. Wobbling is not necessarily a bad thing. So when do you use the wall, and when do you forgo it? Start by noticing what you do most often. If you always use the wall, then it would behoove you to step away from it on occasion to see how you're progressing. (Do this in simpler poses first.) If you never use the wall, give it a try. When the worry about falling disappears, you will have the opportunity to work on the pose in new ways. For example, I have a student who cannot straighten her supporting leg in tree except when she uses the wall. While I am happy to see her work on not holding on, I would like to see her fully using the leg as well, and right now, she can only do that when holding on. The difficulty of the pose can be another determining factor. When you are unfamiliar with a set of instructions, remove the worry about balancing initially by using the wall. As you are more familiar, remove the wall and add a little instability. Lastly, working on balance daily improves balance. And working on balance in a controlled manner is a safe way to work on it. You're not at the top of the stairs or holding something precious. You can always step out of the pose if you feel too unstable. Use the wall. Don't use the wall. Just be clear what your habit is, and figure out why you use or avoid the wall. And take advantage of the different kind of learning that happens either way.  Last week, a student sent me this article from the NY Times called How To Make Your Office More Ergonomically Correct. She sent it because she knows that I get really frustrated with the topic of ergonomics, and articles such as this one are why. The article does mention a few times that being in one position for hours a day five days a week is problematic. But the solutions presented ... ugh. Humans are designed for movement. It is only in recent years that Western culture has created a daily existence that doesn't include much movement. We are now expected to sit at tables to eat, sit in cars to get to work, where we sit at desks, then sit on the commute home, sit at the dining table to eat again, and then sit in front of a television or computer until we lie down to sleep. Numerous health issues arise due to lack of movement. It's not the chairs that are the problem here; it's the lack of movement throughout the day. (And switching to a standing desk where all you do is stand still for the hours you were previously sitting at your desk still means you are not moving.) Sedentary. That's the word for it. We have become sedentary beings. Even if you run every day for 30 minutes, how many hours of the day are you still? It's the equivalent of eating one healthy meal a day, but consuming Cheetohs and Coke continuously for all your other waking hours. It's not enough good food to counter the constant junk food, just as 30 minutes of running is not enough movement to counter all that sedentarism. Numerous studies show that getting up from your chair every half-hour and moving your whole body for one minute has enormous benefit to your overall well-being. Moving your whole body. For one minute. Every half hour. Regularly. That's the recommendation. And yet, there is an entire field studying how to get you to sit still longer. Ergonomics is commonly defined as the refining of design of products for optimizing human use. But in practice, ergonomics is making the best of a bad situation. We need to question the larger cultural structure, not just design better chairs so we can sit longer. If you don't want to read the entire NY Times article (it's not that long and I linked to it above), here's the most egregious example of not understanding the true effects of ergonomically designed offices: "Very few people sit back when they work, but they should, Dr. Hedge said, because when you recline, more of your body weight is supported by your chair, rather than supported by (and also compressing) your spine. " Designing a chair to support your spine actually creates weaker muscles over time. It doesn't reduce compression of the spine. It, in fact, increases the likelihood that you will lose the muscular strength to hold your spine upright. The point of such a chair is to get you to sit still for longer periods of time. Think about those times you watch a movie or even binge watch a few shows. The couch has been holding you up. You finally get up off the couch and every joint is stiff, your circulation is compromised (you might even have a foot that fell asleep), your muscles are tight. That is what happens in that ergonomically-designed desk chair as well. The more the chair does the work for you, the less you will choose to get up and move. The less you get up and move, the less you can get up and move. I teach people to sit forward on a chair. Use your own muscles to hold you upright. Untuck your pelvis. Using your body to hold yourself up is why you do that core work at the gym, isn't it? In fact, sitting like this IS core work all on its own. Feel free to disagree with me on this. I haven't cited my sources, I know. But I have been studying bodies, reading on the subject, and helping people move more and move better for decades. A better designed chair isn't the answer. Period. In my "Thoughts From A Yoga Heretic" blog post, I mentioned fancy yoga as opposed to advanced yoga. I started delineating the two some years ago after one of my regular students said she felt as though she was doing remedial yoga since she had to use the wall to support herself in a particular set of poses. My response was that she was actually doing very advanced work. She was attending to the specific, asymmetrical needs of her body after serious injury. She was hardly doing less than anyone else in class. In fact, using the wall allowed her to work much harder, rebuilding strength, realigning at the hip and knee joints, addressing a newly prevalent twist at the pelvis. Without the wall, she'd simply be making a shape. And that shape would be defined by the muscles that already worked, the current skeletal misalignments.

In fact, that student was/is a very advanced practitioner in my book. She was listening to her body and adapting the work to make changes in her body. I offer that kind of adaptation all the time since my students often skew older and/or injured. But it amazes me how many are stuck on the idea that what I'm offering as an alternative must somehow be remedial if it's not what the group is doing. It is fascinating how many people are determined to stick with the group, even if it hurts, rather than do something different, even if that "something different" will benefit them specifically. So what do I mean by fancy yoga? Google "yoga images" and just look at all the bendy people doing incredible-looking poses in exotic locations. Yes, these are impressive poses. Yes, these may have taken them years to master. But in my experience, the people in those photos represent a tiny fraction of the populace in terms of how they move. Most of us are trying to get a little more flexible, get a little stronger, breathe a little better. And we have to start where we are. When I stand up tall and curve my spine backward and it barely moves and I look like a longbow, that is equivalent to the bendy person who bends backwards from standing and puts her hands on the floor. I'm working at my limit. And I'm working to increase my limit each time I practice. The fact that I don't move as far doesn't make my work any less advanced if I'm working from internal knowledge of my body and seeking improvement. Putting the hands on the floor is fancier looking to be sure, but if each of us are working within our bodies' abilities, my work is no less valuable, no less advanced. So what makes a pose advanced? Emphasizing the shape of the pose de-emphasizes the understanding of the pose. In the above example, do you know if you are actually articulating all along the thoracic spine? Do you know if you are creating the shape from increased lumbar curve (not a safe way to go)? Do you feel energized AFTER the creating that shape (back domes are supposed to uplift energy)? Do you feel crunchy in your mid/lower back? Are you trying to keep up with your neighbor? Are you listening to your limits? That kind of inner questioning, that level of awareness is what makes a pose advanced in my view. Not how far you bend backwards. Fancy poses are fun to look at, fun to figure out what work you'd need to do to achieve them. I'm all for using a fancy pose as a goal. But what makes a pose advanced isn't the pose itself. It's everything you learn along the way, regardless of whether you ever achieve the fanciest version. As I have often said in classes, balancing on one hand with your feet behind your ears while on the edge of a cliff doesn't make you a better yogi. Not being able to do that doesn't make you a lesser yogi. It's all about the work and the self-awareness that you acquire along the way. The more self-awareness, the more specific your practice, the more advanced. Period. I've been teaching yoga for over two decades now. Every time someone who has taken other yoga classes joins my class, one of the first questions they ask me is, "Where will you be standing?" When I tell them I will be moving around the room, this is clearly not a satisfactory answer. But after that first class, when the new student has received actual teaching pertinent to their specific way of moving in their body, the light bulb goes off.

When I started teaching yoga in 1996, I was teaching in YMCAs and corporate offices. There were no stereos, and the portability of music on your phone was far in the future. I never brought a boombox along. During class (Ashtanga at the time) and even during Savasana there was silence. A woman who took my earliest classes later told me that during her first class, the silence was agitating. But by the third week of classes, she realized that the end of yoga class was the only time she ever had silence in her life. She began to relish that time, that peace and quiet.

Twenty years later, I still hold to that practice of not using music. I have even more reasons now than I did then. Every restaurant, every store, every open plaza has piped in music. Most restaurants also have big screen TVs all around. You cannot even get gas without having ads playing at the pump. Silence may be challenging, but it is missing from all our lives. Even when we can get away from the TV, the music, there is the humming of appliances, computers, air conditioning and heating. I may not be able to do anything about the latter, but I can at least lessen the noise by removing music from the practice. Early on I discovered that whenever I did try and use music, that no one kind of music, no one song will resonate with the entire class. I'd rather have the entire class sort their way through silence than make one or two students have to sort their way through a song that agitates rather than soothes. Lastly, I know many yoga teachers pride themselves on their playlist and timing music to coordinate with certain parts of class. I find it very impressive, and if it's the only way you're going to get through a practice, by all means rock out. When I used to run, I admit there were some runs that simply wouldn't have happened without my iPod. But I leave you with the thoughts of a runner who got me to stop running with music playing (most of the time):

I'd posit the same to be true of being on the mat without music. Some of what follows are teachings I was handed by brilliant women and men before me. Some of it I cultivated over my own two-plus decades of teaching.

1) "Just listen to your body" is not a reasonable instruction for beginners. If that person knew what to do, they wouldn't be coming to you. Not to mention the cultural indoctrination to push through, override, or otherwise ignore pain signals that have taught most people to stop listening to their body. (I have written on this topic at length. If you want to read more, click here.) 2) Yoga done to music is fine, but it can prevent someone from learning to listen to their body. It was practiced for decades without any musical accompaniment. It's not that strange. 3) Leading practice is not the same as teaching. Also: Teaching a lot of classes does not equal practicing a lot. 4) If your goal is solely bigger/fancier/bendier movement, that is ego. That is where you are more likely to get hurt. If your goal is to understand the movement and to find the resistance to the movement, that is meditation. 5) Fancy yoga isn't advanced yoga. Many people who do fancy poses could already do something close to those poses before they walked into a yoga studio. 6) Using a wall or a prop is not remedial yoga. Coming out of a pose when you're done is not remedial yoga. In fact, knowing you are not ready for a fancy pose and need a wall or prop; knowing you're at the end of your endurance; that's what I call self-awareness. That's what I call advanced yoga. 7) Yoga classes self-select. If the teacher leads a practice, the students who enjoy that practice will stay. The student who doesn't move the same way the teacher does will decide yoga isn't for them and may never come back. If they keep at it in spite of the challenge, eventually they will get frustrated at lack of progress. Unless they find a teacher who actually teaches, they, too will get frustrated and quit. 8) Irreverence is good. Creating community matters more to me than creating a sacred space of silence. In my experience, laughter promotes breathing. Community decreases competition. Both of which lead to more self-awareness, less pose-envy. 9) Flowing through a series is a wonderful way to practice. But if you never slow down to observe the effects an individual pose, you may never learn which poses are nourishing you, which are helping you breathe or creating ease in a tense area of the body. Likewise, you may never know which poses are depleting or even injuring you. 10) Yoga doesn't cure anything. This will not be a three-sentence post like the other Creativity Break posts.

I cannot believe I already couldn't maintain a daily practice past a week. If I'm honest, I didn't even get past the full week. I counted movement on Day 8 that is part of my normal day as my practice because I did a bit more of it. Yeah, no. Let me give you an idea of what my days look like, movement-wise, and how it's easy to think I've practiced when I really haven't:

I am increasingly teaching about all those ways in which movement throughout the day matters as much if not MORE than a specified period of daily exercise with the remainder spent sitting at a desk or behind the wheel or on the couch. I believe in the vital importance of moving more of your parts in more ways throughout more of the day. And in that respect, I practice what I preach. So why do I want so badly to get back on my mat? Getting on the mat is physical work. It's a chance to really inhabit this body that I've spent a lifetime moving. I've moved onstage and in private. I've moved to tell stories and to teach others. I feel intelligent in my body. I feel graceful. I feel powerful. I learn on the mat and through my body. Getting on the mat has given me insight into injuries (ankle, pelvis, shoulder) and helped me heal them. Getting on the mat can be playful or challenging or calming. It is inward work. I spent my first three decades sweating in dance classes and exercise classes. Movement up until then had either been performance or otherwise externally driven. I got serious about yoga in my late 20s and immediately understood its therapeutic benefits. When running hurt my knees, I got on my mat and figured out at least one of the problems. In my mid-40s, I ran a 10K with my sights set on a half-marathon. The damage to my ankle joint over decades of dance injuries barely survived that 10K. It took the next four years of slow, diligent work on the mat to unwind my movement patterns and re-train my leg, ankle, foot so that I could walk without pain again. Only after all that effort on the mat could I know that running or skipping wouldn't hurt my joints (though I have not tried to run a mile even still). I've spent the past four years using my body knowledge on the mat again, this time to recover from a frozen shoulder. I still don't have full range of motion. And I'm again in the process of unwinding the habits of decades to relearn how to use an even more complicated joint. I have all this experience of utilizing my yoga and body knowledge for my own betterment. I used to inspire my personal practice by studying with my teachers (one now deceased, one far away) and colleagues (all far away since I moved). I used to have a set time of day. I used to have local peers, students who didn't need me to guide them but appreciated sharing space while we all practiced. But now?

I'm starting to wonder if all my (necessary) therapeutic use of yoga has removed play and fun from getting on the mat. I don't have peers to practice with here, which I had before I moved to MN. In Michigan, colleagues and students and I would get together and practice individually in the same space. Maybe I have to create that somehow here. It wouldn't be daily, but it might be enough to motivate me to do it on my own between times. Just sitting with this today, sitting with my unwillingness, digging through why I have and have not practiced during periods of my life, makes it clear that it isn't outer accountability I need. Even declaring a 40-day commitment publicly didn't do it. I lied to myself and to the public by Day 8. The motivation is going to have to come from me. I have looked at my calendar. Rather than writing "Practice" on each day, I carefully chose specific times each weekday and wrote the actual time down. An appointment with myself. Some appointments are 30 minutes, some 45, some 20. I tell my students, it doesn't need to be 90 minutes to be a practice. Time to listen to my own teaching. I do not know if this will work any better than what I've been doing. But I am done with my rebellious, "I won't" attitude. I keep thinking of something a friend shared with me. "Paint until you feel like painting." Yep. I'm going to practice until I feel like practicing. Getting refocused with the Creativity Break. Day 1. [And in case you read the first day of the Creativity Break, here is a photo of the broken Sarasvati that gave me the impulse to do this in the first place.] |

Wool GatheringDeep, and not so deep, thoughts on bodies, movement, yoga, art, shoes, parenting, dogs. You know, life. Archives

October 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed